ارزیابی زیست محیطی استراتژیک (SEA) برای اجتناب از عدم قطعیت تغییرات اقلیمی

14,900 تومانشناسه فایل: 6667

- حجم فایل ورد: 210.5KB حجم پیدیاف: 306.9KB

- فرمت: فایل Word قابل ویرایش و پرینت (DOCx)

- تعداد صفحات فارسی: 18 انگلیسی: 7

- دانشگاه:

- The Danish Centre for Environmental Assessment, Aalborg University-Copenhagen, A.C. Meyers Vænge 15, 2450 København SV, Denmark

- The Danish Centre for Environmental Assessment, Aalborg University, Skibbrogade 5, 1. Sal, 9000 Aalborg, Denmark

- ژورنال: Environmental Impact Assessment Review (1)

چکیده

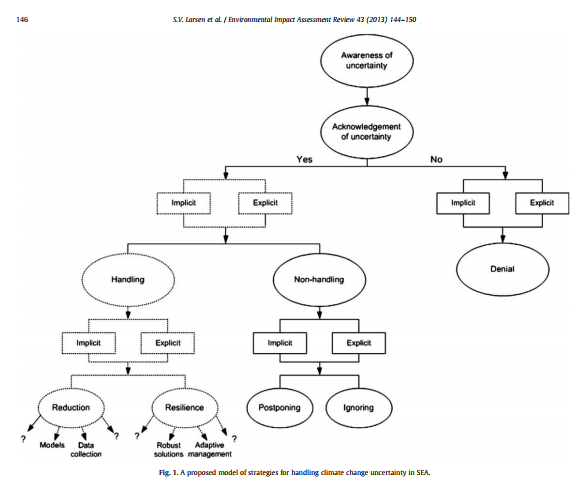

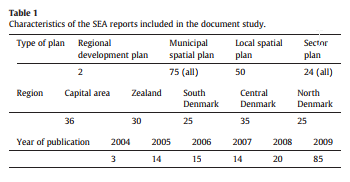

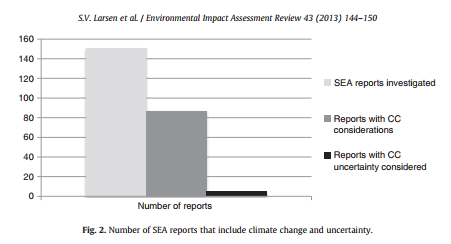

این مقاله مربوط به نحوه ارزیابی استراتژیک زیست محیطی (SEA) عدم قطعیت تغییر اقلیم در سیستم برنامه ریزی دانمارک است. نخست، مدلی فرضی برای نحوه مواجهه و عدم مواجهه با عدم قطعیت در تصمیم گیری تنظیم می شود. این مدل شامل استراتژی های “کاهش”، “انعطاف پذیری”، “انکار”، “نادیده گرفتن” و “به تعویق انداختن” است. سپس 151 ارزیابی استراتژیک زیست محیطی (SEA) دانمارکی با توجه بر میزان پذیرش و ارائه عدم قطعیت تغییر اقلیم تحلیل می شود و درباره یافته های تجربی مرتبط با این مدل مورد بحث قرار گرفته است. یافته ها نشان می دهد که علیرغم انگیزه های لازم برای انجام این کار، در تمام 151 گزارش مورد بررسی به جز 5 گزارش، از عدم قطعیت تغییر اقلیم اجتناب شده است یا نقش آن کم اهمیت جلوه داده شده است. در نهایت، دو روش توضیحی احتمالی برای توضیح این موضوع ارائه شده است: اجتناب از تناقض و نیاز به محاسبه عدم قطعیت.

مقدمه مقاله

عدم قطعیت در ارزیابی استراتژیک زیست محیطی (SEA) به طول دو دهه به عنوان موضوعی مهم در منابع مطرح شده است. به طور مثال در مراحل اولیه SEA، لی و والش (1992) اعلام کردند که “اطمینان از مواجهه رضایت بخش با عدم قطعیت در تمام مراحل فرایند ارزیابی” به احتمال زیاد یکی از مهم ترین مشکلات پیش رو در هنگام طراحی و پیاده سازی SEA است ( لی و والش، 1992، ص 135). از آن به بعد مجموعه منابع مربوط به حوزه عدم قطعیت در ارزیابی تاثیر به طور قابل توجهی افزایش یافته است، به همراه پژوهش های نظری و تجربی که تلاش کرده اند طبقه بندی ریسک ها و عدم قطعیت را طراحی کنند (see, for example, Slovic et al., 1981; Lipshitz and Strauss, 1997; Walker et al., 2003; van der Sluijs et al., 2005; IPCC, 2007; Refsgaard et al., 2013).

رویکرد مبتنی بر طبقه بندی برای درک عدم قطعیت مفید است اما به تنهایی کافی نیست. مولفه کلیدی دیگر مواجهه با عدم قطعیت، آگاهی از نحوه اعلام عدم قطعیت و ادراک افراد از آن است زیرا غالباً درک جوامع علمی، سیاست گذاری و غیر علمی از ریسک و عدم قطعیت بسیار متفاوت است (Frewer, et al., 2003; Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1990; Hellström, 1996; Kuhn, 2000; Patt and Dessai, 2005; Walker, et al. 2003; Wardekker, et al. 2008). آنچه از منابع بر می آید توافق بر سر این موضوع است که به دلیل موازنه بین نیاز علمی به محاسبه دقیق مجهول های اصلی و نیاز سیاست گذاران به تحلیل ساده عدم قطعیت اعلام عدم قطعیت دشوار است.

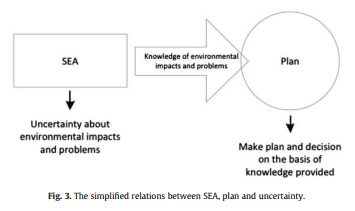

از آنجایی که SEA با شرایط آتی ارتباط دارد، مواجهه با عدم قطعیت یکی از بخش های اجتناب ناپذیر فرایندهای ارزیابی است (Tennøy et al., 2006; Thissen and Agusdinata, 2008; Wilson, 2010) – هرچند میزان و منابع آن ممکن است در موارد مختلف متفاوت باشد. همان گونه که ژو و همکاران بیان می کنند (2011, ص. 538) ” از آنجایی که آینده ذاتا نامشخص است تمام اقدامات مربوط به آینده با عدم قطعیت بالا مواجه هستند و باید آن را از بین برد. همین شرایط برای SEA صادق است“. هر چند پیش بینی ها دارای عدم قطعیت هستند اما ما به ندرت توانسته ایم اطلاعات مورد نیاز یا مطلوب را به دست بیاوریم یا اصلاً موفق به انجام این کار نشده ایم. ژو و همکاران (2011) معتقدند که SEA دارای عدم قطعیت درونی و بیرونی است. عدم قطعیت درونی یعنی تغییرات ناشی از برنامه و تغییرات محیط طبیعی در حال ارزیابی و عدم قطعیت بیرونی یعنی عدم قطعیت در توسعه اجتماعی، اقتصادی، زیست محیطی و سیاست گذاری است. تمام این عوامل برای ایجاد چند نتیجه احتمالی در سیستم پیچیده تحت ارزیابی ترکیب می شوند (Zhu et al. 2011).

به جز بررسی مسئله عدم قطعیت در پیش بینی تاثیر، مواجهه با عدم قطعیت باید ارائه و اعلام است، “خصوصاً در اسنادی که غالباً در دسترس تصمیم گیران، کنشگران دولتی و سایر کنشگران قرار می گیرد” (Tennøy et al., 2006, p. 55) – نظیر گزارش زیست محیطی مورد نیاز هیئت SEA (European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2001).

مواجهه با عدم قطعیت مستلزم آن است که عدم قطعیت طوری اعلام شود “که هم با اقدامات علمی سازگار باشد و هم افراد عادی بتوانند آن را درک کنند” (Petersen, 2002, p. 87).

تغییر اقلیم و پیش بینی آب و هوا در آینده ذاتا نامشخص است (see for example Willows and Connell, 2003; Füssel, 2007; IPCC, 2007). طبق نظر جنکینز (2003, ص. 3)، “آب و هوا در آینده با دو عامل تعیین خواهد شد: میزان انتشار گازهای گلخانه ای و سایر آلاینده های توسط انسان و واکنش سیستم های آب و هوایی به انتشار این آلاینده ها” و هر دوی این عوامل و نیز ارزیابی تاثیر تغییر اقلیم تحت تاثیر عدم قطعیت هستند (Jenkins and Lowe, 2003). برای مثال، در گزارش سازمان محیط زیست اروپا با عنوان آثار تغییر اقلیم اروپا به این موضوع اشاره می شود که نحوه عملکرد سیستم آب و هوایی و نحوه تاثیر گذاری نیروهای موثر جامعه بر سیستم آب و هوایی نامشخص است (Erhard, 2008). به طور خاص، وضعیت انتشار آلاینده ها در آینده تحت تاثیر عواملی نظیر جمعیت، رشد اقتصادی و توسعه تکنولوژیکی است (Jenkins and Lowe, 2003). IPCC (2005, ص. 1) عدم قطعیت را به سه دسته تقسیم می کند:

- پیش بینی ناپذیری؛ در ارتباط با رفتار انسانی غیر قابل پیش بینی و مولفه های بی نظم سیستم های پیچیده

- عدم قطعیت ساختاری؛ در ارتباط با مدلسازی نامناسب، چارچوب های مفهومی و مرزهای سیستم

- عدم قطعیت ارزش؛ در ارتباط با کمبود داده ها و پارامترها و دقت ناکافی

فرضیه عدم قطعیت موجود در ارزیابی تاثیر برای تغییر اقلیم و فرایندهای پیچیده طبیعی و اجتماعی موجود بسیار مهم و حیاتی است. در محیط اروپا، ادغام تغییر اقلیم در SEA به لحاظ قانونی هم الزامی است (European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2001). با وجود این، بررسی پایش 5 ساله دستورالعمل SEA نشان می دهد که به طور کلی کشورهای عضو تغییر اقلیم را در SEA ادغام نکرده اند و “هنوز برای بررسی تنوع زیستی و تغییر اقلیم در SEA باید پیشرفت های بیشتری انجام شود” (COWI، 2009، ص 42). برای بررسی عدم وجود این یکپارچگی، دستورالعمل جدیدی درباره تغییر اقلیم و ارزیابی تاثیر در سال 2013 منتشر شد European Commission, 2013). لارسن و همکارانش (2012) متوجه شدند که در محیط دانمارک تغییر اقلیم بیش از پیش در SEA در نظر گرفته می شود اما به طور خاص انطباق با تغییر اقلیم کمتر مورد توجه قرار گرفته است. اما در محیط بین المللی، مطالعات دیگر به این نتیجه رسیده اند که انطباق با تغییر اقلیم به شکل بهتری در SEA ادغام شده است (see for example Posas, 2011).

بر اساس ملاحظات فوق، برداشت این مقاله این است که عدم قطعیت موضوع مهمی است که SEA باید به آن بپردازد و در حال حاضر، نویسندگان نمونه هایی را مشاهده می کنند که در آن ها عدم قطعیت به عنوان مانعی برای مواجهه با تغییر اقلیم عمل می کند. به ویژه در دانمارک بر اساس بحث عدم قطعیت، تغییر اقلیم به عنوان یکی از مشکلات فرایند تهیه طرح های مدیریت حوضه رودخانه ها در سطح کشور کنار گذاشته شده است (Larsen, 2010). علاوه بر این، شهرداری های دانمارک که در حال تهیه طرح های اقدام مدیریت حوضه رودخانه هستند پیچیدگی، عدم قطعیت و افق های زمانی طولانی را به عنوان موانع اصلی مواجهه با تغییر اقلیم بیان می کنند (Larsen, 2010). بر این اساس، به اعتقاد ما بررسی مسئله عدم قطعیت تغییر اقلیم در ارتباط با برنامه ریزی از طریق SEA به عنوان یکی از ابزارهای برنامه ریزی و پشتیبانی از تصمیم، ارزشمند است.

هدف اصلی این مقاله این است که آیا عدم قطعیت تغییر اقلیم به صراحت در اقدام SEA در دانمارک پذیرفته و ارائه شده است و این کار چگونه انجام شده است. بدین منظور، در بخش 2 یک مدل نظری برای تحلیل ارائه می شود. از این مدل در بخش 3 و 4 استفاده می شود که در آن بررسی مستندات 151 گزارش SEA ارائه می شود. بخش نهایی دو توضیح نظری برای جلوگیری از عدم قطعیت، اجتناب از تعارض و نیاز به محاسبه عدم قطعیت ارائه می دهد.

ABSTRACT Avoiding climate change uncertainties in Strategic Environmental Assessment

This article is concerned with how Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) practice handles climate change uncertainties within the Danish planning system. First, a hypothetical model is set up for how uncertainty is handled and not handled in decision-making. The model incorporates the strategies ‘reduction’ and ‘resilience’, ‘denying’, ‘ignoring’ and ‘postponing’. Second, 151 Danish SEAs are analysed with a focus on the extent to which climate change uncertainties are acknowledged and presented, and the empirical findings are discussed in relation to the model. The findings indicate that despite incentives to do so, climate change uncertainties were systematically avoided or downplayed in all but 5 of the 151 SEAs that were reviewed. Finally, two possible explanatory mechanisms are proposed to explain this: conflict avoidance and a need to quantify uncertainty.

Introduction

Uncertainty in Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) has been a recurrent theme within the literature for well over two decades. In the early stages of SEA, for example, Lee and Walsh (1992) noted that “ensuring that uncertainty is satisfactorily handled at each stage in the assessment process” is likely to be one of the most significant challenges faced when developing and implementing SEA (Lee and Walsh, 1992, p. 135). The body of literature within the field of uncertainty in impact assessment has grown substantially since then, with theoretical and empirical work that has attempted to develop a typology of risks and uncertainty (see, for example, Slovic et al., 1981; Lipshitz and Strauss, 1997; Walker et al., 2003; van der Sluijs et al., 2005; IPCC, 2007; Refsgaard et al., 2013).

The taxonomic approach to understanding uncertainty is useful, but insufficient in and of itself. Another key component of handing uncertainty is making sense of how people communicate and perceive uncertainty, since there are often large differences between the scientific, policy making, and non-scientific communities in their understanding of risk and uncertainty (Frewer, et al., 2003; Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1990; Hellström, 1996; Kuhn, 2000; Patt and Dessai, 2005; Walker, et al. 2003; Wardekker, et al. 2008). What has emerged from the literature is a consensus that communicating uncertainty is tricky, due to the trade-offs between scientific needs for precise enumeration/qualification of the underlying unknowns and policy-making needs of simplified analysis that does not demand detailed familiarity with the underlying science basis for policy decisions.

Since SEA is concerned with future states, dealing with uncertainty is an unavoidable part of assessment processes (Tennøy et al., 2006; Thissen and Agusdinata, 2008; Wilson, 2010) — though the degree and sources might be different from case to case. As stated by Zhu et al. (2011, p. 538) “Since the future is inherently uncertain, all exercises about the future are facing, and should cope with great uncertainty. The same situation happens to SEA”. While uncertainty is involved in prediction, we very rarely, or never, succeed in having the information required or wanted. Zhu et al. (2011) have argued that there are both internal and external uncertainties involved in SEA. Internal in terms of changes brought on by the plan and changes in the natural environment being assessed and external in terms of uncertainty in social, economic, environmental, and policy development. All of these factors combine to yield a number of possible outcomes within the complex system under assessment (Zhu et al. 2011).

Apart from considering the question of uncertainty in impact predictions, handling uncertainties also involves presentation and communication, “especially in the documents that most often reach decision-makers, the public and other actors” (Tennøy et al., 2006, p. 55) — such as the environmental report required by the SEA Directive (European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2001).

Handling uncertainty requires communicating uncertainties in a way “…which both match scientific practice and can be understood by lay people” (Petersen, 2002, p. 87).

In the European Union Directive on SEA, the provisions for the content of environmental reports state that they should include “an outline of the reasons for selecting the alternatives dealt with, and a description of how the assessment was undertaken including any difficulties (such as technical deficiencies or lack of know-how) encountered in compiling the required information” (European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2001, Annex 1, L 197/36). One of the difficulties encountered in an assessment can be uncertainty in different forms, including the uncertainty of the consequences of climate change in relation to the plan or programme. In the recently published EU Guidance on the integration of climate change into SEA, uncertainty is mentioned as one of the challenges that must be dealt with when working with climate change in SEA (European Commission, 2013). It is important to note that consideration of climate change issues should cover not only the impacts of the plan or programme on climate change such as calculations of greenhouse gas emissions, but also the climate change induced impacts on the plan and programme themselves, for example increased flooding events (Larsen and Kørnøv, 2009). SEA is particularly well suited for taking into account climate change objectives as it allows a broader strategic scope and also better consideration of cumulative effects associated with plans and programmes in a given sector or region.

The provisions of the directive have been translated directly into the Danish legislation on SEA (LBK nr 1398, 2007, Annex 1 (h)). In Denmark, they are supplemented with guidance stating that the potential impacts of a plan may be uncertain, for example due to the geographical extent of the plans and the range of activities that they may encompass. Also, it is stated that any assumptions made in the assessment should be made clear (VEJ nr 9664, 2006, pp. 45–6). From the above, it is clear that there is emphasis in the Danish guidance on uncertainty of the impacts resulting from the plan, rather than uncertainty of impacts on the plan, such as those of climate change.

Climate changes and the predictions of future climate are inherently uncertain (see for example Willows and Connell, 2003; Füssel, 2007; IPCC, 2007). According to Jenkins and Lowe (2003, p. 3), “the climate of the future will be determined by two factors: the amount of man-made emissions of greenhouse gasses and other pollutants, and the response of the climate system to these emissions” and both of these factors as well as impact assessments of climate changes are influenced by uncertainty (Jenkins and Lowe, 2003). For example, in the report Impacts of Europe’s Changing Climate from the European Environment Agency, it is pointed out that there is uncertainty regarding how the climate system functions and how the driving forces of society will affect the climate system (Erhard, 2008). Specifically, future emission profiles are driven by factors such as population, economic growth, and technological development (Jenkins and Lowe, 2003). The IPCC (2005, p. 1) breaks down uncertainty into three categories:

- Unpredictability; related to unpredictable human behavior, and chaotic components of complex systems

- Structural uncertainty; related to inadequate modelling, conceptual frameworks, and system boundaries

- Value uncertainty; related to lack of data and parameters and inappropriate resolution

The uncertainty premise embedded in impact assessment is highly relevant and critical for climate change and the complex natural and social processes involved. In the European context, integration of climate change in SEA is also legally required (European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2001). In spite of this, the 5-year monitoring review of the SEA Directive reveals that member states in general lack climate change integration and “that much progress is still to be made to address biodiversity and climate change in SEAs” (COWI, 2009, p. 42). In order to address this lack of integration, new guidance on climate change and impact assessment was published in 2013 (European Commission, 2013). In a Danish context, Larsen et al. (2012) find that climate change is increasingly considered in SEA, but that especially climate change adaptation is lacking attention. In an international context, however, other studies have found climate change adaptation better integrated in SEA (see for example Posas, 2011).

Based on the above considerations, this article is motivated by the perception that uncertainty is an important issue for SEA to deal with, and the authors currently see examples where uncertainty acts as a barrier for dealing with climate change. Prominently, in Denmark, climate change has been excluded as an issue in the process of preparing river basin management plans at state level based on an argument of uncertainty (Larsen, 2010). Furthermore, the Danish municipalities who are to prepare river basin management action plans state complexity, uncertainty, and long time horizons as being among the main barriers for dealing with climate change (Larsen, 2010). On this basis we find it worthwhile to explore the issue of climate change uncertainty in relation to planning through SEA as a planning and decision support tool.

The main purpose of this article is to investigate whether and how climate change uncertainties are acknowledged and presented explicitly in SEA practice in the case of Denmark. For this purpose, in Section 2 a theoretical model is developed for analysis. This model is used in Sections 3 and 4 where a document study of 151 SEA reports is presented. The final section offers two theoretical explanations for avoiding uncertainty, conflict avoidance and a perceived need to quantify uncertainty.

- مقاله درمورد ارزیابی زیست محیطی استراتژیک (SEA) برای اجتناب از عدم قطعیت تغییرات اقلیمی

- عدم قطعیت تغییر اقلیم در اقدام SEA

- اجتناب از عدم قطعیت تغییرات اقلیمی در استراتژیک ارزیابی زیست محیطی

- پروژه دانشجویی ارزیابی زیست محیطی استراتژیک (SEA) برای اجتناب از عدم قطعیت تغییرات اقلیمی

- اجتناب از تغییر نامطمئن آب و هوا در ارزیابی راهبردی زیست محیطی

- پایان نامه در مورد ارزیابی زیست محیطی استراتژیک (SEA) برای اجتناب از عدم قطعیت تغییرات اقلیمی

- تحقیق درباره ارزیابی زیست محیطی استراتژیک (SEA) برای اجتناب از عدم قطعیت تغییرات اقلیمی

- مقاله دانشجویی ارزیابی زیست محیطی استراتژیک (SEA) برای اجتناب از عدم قطعیت تغییرات اقلیمی

- ارزیابی زیست محیطی استراتژیک (SEA) برای اجتناب از عدم قطعیت تغییرات اقلیمی در قالب پاياننامه

- پروپوزال در مورد ارزیابی زیست محیطی استراتژیک (SEA) برای اجتناب از عدم قطعیت تغییرات اقلیمی

- گزارش سمینار در مورد ارزیابی زیست محیطی استراتژیک (SEA) برای اجتناب از عدم قطعیت تغییرات اقلیمی

- گزارش کارورزی درباره ارزیابی زیست محیطی استراتژیک (SEA) برای اجتناب از عدم قطعیت تغییرات اقلیمی