Outline

- Abstract

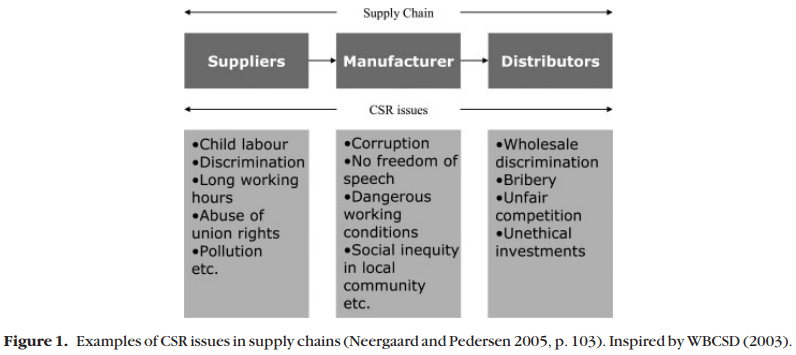

- Introduction: Csr in Global Supply Chains

- Theoretical Perspective

- Agency Problems and Codes of Conduct

- Safeguards/protective Mechanisms

- Safeguarding Mechanisms at Ikea

- Direct Sanctions

- Goal Congruence

- Third-Party Intervention

- Trust

- Reputation Effects

- Conclusion: Managing Codes of Conduct in Global Supply Chains

- Future Research

- References

رئوس مطالب

- چکیده

- مقدمه: CSR در زنجیره های تامین عمومی

- مشکلات وساطت و آئین نامه های رفتاری

- مکانیزم های حفاظتی

- مکانیزم های محافظت در IKEA

- تحریم های مستقیم

- تناسب هدف

- مداخله شخص ثالث

- اعتماد

- تاثیرات اعتبار

- نتیجه گیری: مدیریت کدهای رفتاری در زنجیره های تامین عمومی

- تحقیق آینده

Abstract

- In the wake of globalization, companies are becoming increasingly aware of the social and environmental aspects of international production. Companies of today not only have to be profitable, but they also have to be good corporate citizens. In response to the increasing societal pressure, many companies adopt the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) by introducing codes of conduct that are expected to ensure socially responsible business practises throughout the chain—from supplier of raw materials to final end‐users.

- However, there are several challenges to the management and control of codes of conduct in global supply chains. Active commitment is a precondition for the successful implementation of the codes, but the incentive to comply with the codes does not necessarily extend to all the actors in the chain. Moreover, it is difficult to enforce codes of conduct in global supply chains, because the involved companies are separated geographically, economically, legally, culturally and politically. In consequence, introducing codes of conduct in global supply chains raises a series of agency problems that may result in non‐compliance.

- Realizing that non‐compliance can have severe consequences for the initiator (due to consumer sanctions, negative press, capital loss, government interventions, damaged brand etc.), the article analyses how the interests of the actors in the supply chain can be aligned with the terms of the codes. IKEA is used as a ‘best case’ example to illustrate how codes of conduct can be effectively managed in the supply chain.

Conclusion: managing codes of conduct in global supply chains

Codes of Conduct can be seen as a contract between the company and society. The company promises to fulfil its societal obligations as a corporate citizen by being profitable, law abiding and ethical (cf. Carroll and Buchholtz, 2003, p. 40). In a global supply chain perspective, however, where part of the production process is outsourced to companies in different geographic, cultural and institutional settings, such a promise cannot be made without the active commitment of all actors involved. However, Codes of Conduct are often vague and poorly monitored, which leaves some room for interpretation—and opportunism in the form of non-compliance.

Realizing that this non-compliance constitutes a threat to the companies, which promote themselves as socially responsible by developing Codes of Conduct, it is becoming increasingly important to develop new means to manage and control inter-organizational relationships.

In the previous sections, this article has discussed some of the problems, which are associated with ensuring code compliance throughout the chain, and has tried to give an overview of some of the basic protective mechanisms, which can safeguard the buyer from non-compliance with Codes of Conduct in global supply chains. The discussion of safeguards can be summarized into a number of general recommendations to companies implementing Codes of Conduct in global supply chains:

- Direct sanction is a very effective safeguard if the buyer is the dominant partner in the business relationship (Unless non-compliance is very likely to go undetected, of course) (Koch, 1995, p. 14). The governance of code implementation can be relaxed if the exchange relationship is very important to the supplier (cf. Hill and Jones, 1992, p. 135). An analysis of the power structure and the resource dependency in the chain must be included in the planning of safeguard mechanisms. A description of legitimate direct sanctions should be included in the formulation of a Code of Conduct.

- Metaphorically speaking, direct sanction/ exit is the stick whereas a bottom up/voice approach can be seen as the carrot (Helper, 1990, p. 6). Codes of Conduct are often implemented in a top–down way, but an increased involvement of the supplier in the planning and implementation of the codes might reduce the risk of opportunism because it aligns interests and establishes commitment to the initiative throughout the supply chain.

- Goal congruence can be achieved through joint investments and/or medium and long term delivery contracts conditioned by code compliance. For instance, the buyer can support investments in socially and environmentally friendly technology and offer training and technical assistance in social and environmental management.

- Trust can be an effective safeguard, especially in long-term relationships in which the buyer and the supplier have accumulated a thorough knowledge of each other. However, it is difficult to separate opportunistic and trustworthy suppliers, and therefore trust must be combined with other safeguards.

- Third-party monitoring and enforcement can be an effective protective mechanism. Moreover, third-party verification can be a means to improve the overall credibility of the codes. Codes of Conduct are often met with some scepticism, and failure to ensure compliance with the codes might erode the overall credibility of the buyer’s voluntary initiative. In general, third-party involvement can be recommended in the implementation of Codes of Conduct.

- Reliance on reputation effects depends on the costs and benefits of opportunistic behaviour. Reputation is a highly relevant safeguard when the supplier is dependent on future co-operation with the buyer, and/or the buyer can harm the supplier by communicating non-compliance to other relevant actors, for example in business networks. As with direct sanctions, the planning of codecompliance mechanisms requires an analysis of the relationship with the suppliers in the chain.